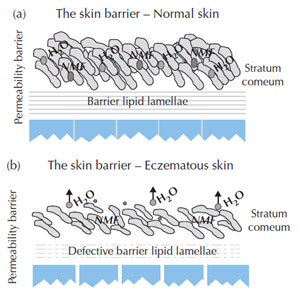

Biology and pathophysiology of eczema Atopic eczema occurs as a result of the interaction of environmental factors with an abnormal immune system in a genetically predisposed individual (Cork, 1997). These genetic changes cause an altered immunological response to antigens and as a result immunoglobulin (Ig) E or IgE is produced. Abnormal T-helper (TH) lymphocytes play a key role in the disease interacting with Langerhans cells which raises IgE and interleukin levels and reduces interferon levels (INF-γ); this leads to an upregulation of pro-inflammatory cells (Buxton and Morris-Jones, 2009). In atopic individuals, IgE binds to mast cells and an antigen response causes mast cell degranulation resulting in the release of pro-inflammatory mediators and hence the development of inflamed eczematous lesions (McFadden et al., 1993). In addition, this response can only occur due to the additional genetic alteration of the epidermal barrier, which allows the penetration of antigens (Cork, 1997). The primary defect is the reduced barrier function (e.g. from filaggrin mutations) which allows protein antigens to get into the skin; leucocytes then prime T-helper cells to become T2 helper cells, which then release interleukin 4, 5 and 13, leading to high IgE levels and other effects (Healy, E., University of Southampton, Southampton, pers. comm.). The complex relationship between the epidermal barrier dysfunction in atopic eczema and the interaction between genes and the environment is usefully summarised in (Cork et al., 2006). The normal skin barrier has lipid lamellae which keep high levels of water within the corneocytes and together with high levels of natural moisturising factors (NMFs), e.g. urea, lactic acid and urocanic acid that maintain the skin’s protective features and keep the skin elastic and smooth (Cork, 1999). Skin barrier changes in eczematous skin include the breakdown of lipid lamellae from around the corneocytes and a decrease of up to 80% of the levels of NMF. In addition, genetic changes in atopic eczema of the genes (including filaggrin and protease) responsible for the structure of the skin barrier (stratum corneum) result in decreased levels of NMF within the stratum corneum (Palmer et al., 2006). This results in water loss from the corneocytes, with shrinking and cracking permitting penetration of irritants and allergens and triggering the inflammatory response. The differences between normal skin and eczematous skin barriers are illustrated in Figure 9.5.

Staphylococcus aureus is an environmental trigger in atopic eczema as it flourishes in eczematous skin. Bacterial colonisation of the skin with Staphylococcus aureus will result in active eczema with visible signs of infection, such as weeping, crusting and pustules, present in the skin. Therefore Staphylococcus aureus will exacerbate and sustain eczema. There are several mechanisms that support this physiological response in eczema:

| ||

© 2025 Skin Disease & Care | All Rights Reserved.