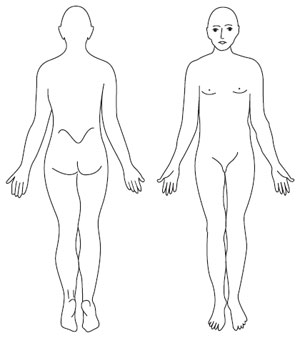

Body surface area As highlighted in the previous section, the skin covers an extensive surface area, covering approximately 2 m2 of the body (Tortora and Derrickson, 2006). An important element of skin assessment is to determine the extent to which the body surface area (BSA) is affected by the disease and the nature and pattern of lesions. It is commonplace to use a simple body map pro forma in clinical practice to document the distribution of rashes and track their variations with time. Figure 3.1 shows a body map depicting the front and back of the body, where the distribution of lesions (the affected area) may be crudely reflected by the degree of shading completed. It is possible to record on the body map the BSA affected, as a percentage. The BSA can be estimated in various ways (Ashcroft et al., 1999). The use of the flat hand palm provides an indicator of 1% of total BSA, whilst often accepted in clinical practice technical estimates put the area as up to 0.76% of the BSA. Another approach, the rule of nines, estimates different areas of the body comprising of 9% coverage for each of the following: head, anterior trunk (upper and lower each 9%), posterior trunk (upper and lower each 9%), each leg (anterior and posterior each 9%), each arm (4.5% each) and genitalia (1%) (see Figure 3.2). However, untrained observers tend to overestimate the extent of lesions, such as small psoriasis plaques. A challenge in dermatological assessment is securing sufficient consensus on the area of skin affected by disease, which is the variation between assessors or observers. High inter-observer variability is a problem of calculating BSA amongst clinicians (Ashcroft et al., 1999). Clinical monitoring of the course of disease over time may involve the documentation of the distribution of the affected area of skin; this is achieved by shading the affected area. Increasingly, estimates of body surface are used in the assessment of disease severity measures, such as the PASI or Psoriasis Area Severity Index, which are discussed in more detail later in this section. Errors made in the estimation of BSA may well affect the severity score and, in turn, this may have implications for treatment decisions based on clinical protocols. For this reason, the estimation of BSA and the related calculation of severity measures require training and oversight within clinical teams, to ensure practitioner achieve a satisfactory standard of consistency and accuracy. Understanding and describing lesions With the very high number of dermatological diagnoses, it is particularly useful to be able to understand and systematically describe the different features and observable patterns of the underlying lesion or rash. This has the benefit of highlighting its observable features and enabling referral to other health professionals without a diagnosis. However, if undertaken effectively it should be an indication of a differential diagnosis for those with the appropriate training. Documenting the appearance of a lesion or rash can be challenging given their pattern of distribution and the sublety of their surface features. As such, it is necessary to gain familiarity with the typical types of lesions seen and rash patterns; these are introduced below. The process of describing lesions is therefore a precursor to making a full assessment and any subsequent differential diagnosis or the basis for referral. Guidance on how to describe skin lesions is summarised in Table 3.2.

| ||||||||||||

© 2025 Skin Disease & Care | All Rights Reserved.